|

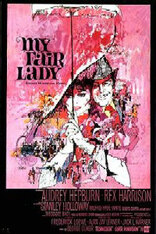

One of the dozens of things I keep track of in feature films is the language used by and in reference to female characters, both women and girls. My Fair Lady (1964), a musical based on George Bernard Shaw’s play, Pygmalion, boasts few named female characters that appear in more than one scene (Audrey Hepburn, Gladys Cooper, Mona Washbourne and Isobel Elsom), however, they all have assertive moments, Hepburn in particular. It won the Oscar, BAFTA and Golden Globe awards for best picture, as well as several other awards. The most enjoyable thing about My Fair Lady, for me, is the uncommonly assertive language used by the lead female, named Eliza Doolittle (Hepburn), a street vendor who accepts to live with a phonetics professor (Rex Harrison as Henry Higgins) for a wager he makes that he can pass her off as a member of the British upper class in six months’ time. He is a brute with her, and she repeatedly stands up to him. For example, she says to him, “I have a right to be here if I like, same as you,” “You’re no gentleman!”, “You don’t care for nothin’ but yourself!”, “You’re a great bully, you are!”, “I won’t stay if I don’t like, and I won’t let nobody wallop me!”, “Because I want to smash your face! I could kill you, you selfish brute!”, “Don’t you hit me!” and “Do you want me back only to pick up your slippers and put up with your tempers and fetch and carry for you?” She also sings to him, “I shall not feel alone without you. I can stand on my own without you” and tells him, “I can’t talk to you. You always turn everything against me. I’m always in the wrong. But don’t be too sure that you have me under your feet to be trampled on and talked down.” Also, she says of him: “he’s no gentleman,” “[…] he treats me as if I was dirt,” “Don’t let him speak to me like that” and “I should never have known how ladies and gentlemen behave if it hadn’t been for colonel Pickering. He always showed me that he felt and thought about me as if I was something better than a common flower girl.” Talk about progressive speech! Cinema has rarely given female moviegoers a woman who stands up to her oppressor the way Eliza does. It's a shame that the ending, a very short scene, has Eliza returning to Higgins. It conveys the regressive message that, at the end of the day, it is acceptable for men to treat women badly. Hepburn's assertive speeches aren't the only ones. Mona Washbourne, too, is assertive. For instance, she says to Harrison, her employer, “You can’t walk over everybody like this” and “Oh, do be sensible, sir.” And Gladys Cooper is more assertive than many 21st century female characters. When told of her son’s behaviour she says, “This is simply appalling. I should not have thrown my slippers at him; I should have thrown the fire iron.” She also values Hepburn and says of her to Harrison, “Eliza came to see me this morning, and I was delighted to have her. And if you don’t promise to behave yourself I must ask you to leave.” Rarely has cinema given us women who stand up for other women like this. Also, when Hepburn leaves him Cooper says to herself, “Bravo, Eliza!” This type of assertive speech from female characters is something female viewers are still not getting enough of, over fifty years later. I look forward to sharing my findings about the language used in mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries in my upcoming film guide for women. © 2019 Alline Cormier

1 Comment

Gabrielle (2013) is a unique and heartwarming Québécois drama full of singing that has much to offer female viewers. It is set in Montréal and tells the story of Gabrielle (Gabrielle Marion-Rivard), a 22-year-old woman with Williams syndrome, who struggles to gain the necessary independence to make her own decisions, particularly concerning her right to have a boyfriend. It is entertaining and scores very well for women’s presence and voice, likely because it was written and directed by a woman (Louise Archambault). One of the best things it has to offer female viewers is a congenial relationship between sisters. Indeed, Marion-Rivard and her sister, Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin, are supportive, affectionate and loving. They hug, hold hands, press their heads together and blow kisses to each other. They spend time together (Désormeaux-Poulin takes Marion-Rivard places on her scooter). Moreover, this is not the only congenial relationship between women. Marion-Rivard and her co-worker hug and Isabelle Vincent hugs and kisses her daughters. In fact, women hug seven times in Gabrielle. This much true affection between women is rare in film. There are other uncommon inclusions, such as assertive female characters, praise for women, etc. Nice touches include a female chamber ensemble, a concert by Robert Charlebois and the Les Muses choir and the overarching message that everyone has a right to be loved. It is easy to see why this delightful drama was chosen as the best picture at the Canadian Screen Awards in 2014.

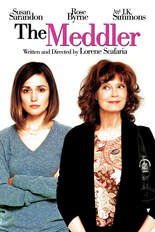

© 2019 Alline Cormier One of the dozens of things I keep track of in mainstream movies is the language used in reference to female characters, both women and girls. Part of the reason for this is that language is very revealing about filmmakers. It tells us a lot about how well or poorly they think of women. The Meddler (2015), a romantic comedy written and directed by Lorene Scafaria, includes at least four named female characters that appear in more than one scene. It scores very well for women’s presence and voice and has much to offer female viewers, including congenial relationships between females (four generations!). It is always a good sign when a movie includes several congenial relationships between females. One of the things that struck me most about this movie, however, was the language used by its characters. It demonstrates respect for women. In The Meddler women are not referred to as honey, sweetheart, broads, dames or chicks. No woman is called a b*tch or told to f*ck off. Instead a woman is praised (Susan Sarandon calls Rose Byrne a genius and a man calls her a very smart girl). A man apologizes for the language he uses in front of a woman (a policeman who talks about a naked man, without using any coarse language, says to Sarandon, “Oh, pardon my language”). A father shows respect for his daughter’s wishes (J.K. Simmons tells Sarandon, “Lizzie doesn’t want me to call her anymore. I have to respect that”). A woman is even encouraged to talk (when Sarandon asks, “Am I asking too many questions?” Simmons replies, “No”). These are rare inclusions for Hollywood movies. You won't find these things in a Quentin Tarantino film, to name just one male director whose female characters are treated like garbage. Having women work behind the camera makes a significant difference in terms of what a movie has to offer female viewers (both women and girls). I look forward to sharing my findings about the language used in mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries in my upcoming film guide for women.

© 2019 Alline Cormier |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed