|

Last week I made time to sew the I ‘heart’ JK Rowling banner I had been contemplating ever since Amy Hamm and Chris Elston put up their I ‘heart’ JK Rowling billboard in Vancouver (earlier this month). When they did that I thought it would be wonderful to see similar initiatives all over Canada—an outpouring of love and support from coast to coast to coast. Since I can’t afford a billboard I decided I would make a banner. It took me two days, but it was worth it. I used two old bedsheets and quite a lot of scrap fabric (the heart was cut from Christmas fabric).

The first photo op to present itself was in Banff, Alberta. It was windy and I couldn’t get the stakes into the hard ground—littered with elk poo—so I leaned my banner against the tennis courts of the Banff Springs Hotel, snapped a few pictures and moved on to a location closer to downtown Banff. For the second set of pictures I had a paper clip, which came in handy to attach my sagging banner to a fence. These ones show the Bow River and the town’s bridge in the background. It was such a beautiful, sunny day—really ideal for a spot of activism. An older couple walking past stopped and the woman asked, in a worried voice, if anything had happened to Joanne Rowling. I reassured her that she hadn’t passed away and I was just doing this as a thank you to her for standing for women and girls. We talked a bit about how we both love her writing and she and her partner moved on. All in all it was a positive experience and no one said anything negative to me about the banner in either location. I’m looking forward to setting it up in other towns. Ideally we would see at least one billboard/banner in each of the provinces and territories this month. So please get painting, sewing or ordering! B.C. and Alberta have been represented. Now it’s Saskatchewan’s turn if we’re moving West to East on this initiative. If you make a banner send me a picture. I’d love to see it! Copyright © 2020 Alline Cormier

2 Comments

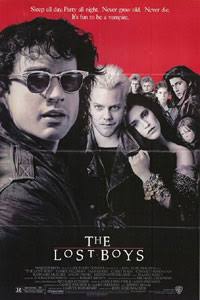

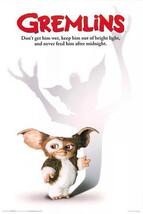

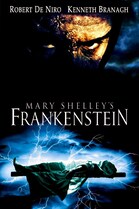

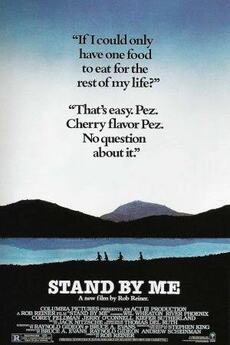

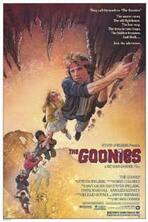

The Lost Boys is an R-rated horror movie that runs just over one and a half hours. It was directed by Joel Schumacher and the screenplay, which is based on a novel by Janice Fischer, was written by Fischer, James Jeremias and Jeffrey Boam. It made over US$32 million at the U.S. box office (unadjusted dollars). It is one of the rare horror movies I find enjoyable, and this is mainly due to its many humorous moments. Originality is another thing it has going for it. This isn’t the usual old-man-preying-on-much-younger-women vampire story. Consider the tagline: “Sleep all day. Party all night. Never grow old. Never die. It’s fun to be a vampire.” When The Lost Boys was released it felt like a fresh cinematic take on vampires. It came out five years before Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) and likely renewed audiences’ appetite for vampire movies. I suspect most North American Gen-Xers are familiar with it, but for everyone else I will provide some context before diving into what it has to offer female viewers. The Lost Boys tells the story of two teenage brothers, Michael and Sam, played by Jason Patric and Corey Haim respectively, who must deal with a group of vampires that Patric befriends when the brothers and their mother, played by Dianne Wiest, move to their grandfather’s house in Santa Carla, California, from Arizona after her divorce. The handful of vampires Patric starts hanging out with after dark are led by Kiefer Sutherland. The year before we had seen him in Stand by Me and the next year he was in Young Guns—both highly entertaining movies. This Sutherland is the grandson of Tommy Douglas, the Premier of Saskatchewan who was behind Canada’s first universal health insurance system—one of the things that makes Canada great. But I digress. Getting back to the boys, Corey Haim also befriends some teenagers: the Frog brothers, fighters for truth, justice and the American way while working in their parents’ comic book store. This second set of brothers is played by the camo-sporting Corey Feldman and Jamison Newlander. As another aside, Corey Haim was a Canadian actor from Toronto who had appeared in Lucas the year before. Corey Feldman has claimed publicly that Charlie Sheen raped Corey Haim on the set of Lucas when he was just 13 years old. Haim struggled with drug addiction in adulthood and died at the age of 38. I should mention that my film commentaries are not full movie reviews. Typically I shine a spotlight on just one aspect of the movie, for example, language, the sexualization of the female characters or violence against women and girls. For The Lost Boys I am going to focus on the progressive inclusions that relate to Dianne Wiest’s character, named Lucy. Also, I do not know if she is named Lucy as a nod to Bram Stoker’s novel (Dracula) but if you have read something about that please leave me a comment. I have not read any interviews with Janice Fischer. Since I am always very interested in how a movie scores for women’s presence and voice I will just point out quickly that it scores moderately well. There are only two named female characters (Wiest and Jami Gertz, Patric’s love interest), and they never speak. Also, there is no congeniality between women, women are harmed and Gertz is sexualized. In film women are often treated with little regard. The ‘80s and ‘90s, however, gave us a more progressive treatment of female characters and in some ways The Lost Boys is more progressive than many 21st century movies and has more to offer female viewers than many movies in the horror genre. I credit Janice Fischer with this. There is little focus on women’s looks here and relatively little sexualization of the female characters. The Lucy character and inclusions relating to her are of particular interest to me because they likely got little attention anywhere else. The first thing worth mentioning is the focus on the impoverished state she finds herself in after leaving her husband. There are undoubtedly scores of women who can relate to this situation. Her ex is alive but makes no appearance here. We only get Wiest’s side of the story. This is unusual. It is more common to be given the man’s version of events. Here we are shown a single mom struggling to raise her sons, so poor that she has to move back in with her father. We also see the 40-year-old getting a job as a cashier. The filmmakers lead us to sympathise with her and feel that she was unjustly treated. It may not seem like a big deal but more often than not filmmakers portray men’s blameworthy behaviour towards women approvingly, rather than disapprovingly. Secondly, and this, too, may not seem like a big thing but it is, Wiest sits down to a supper Edward Herrmann made her. Even though he made it off-screen this is still an improvement over what we usually get. Most often in film it is women who serve males food and drink. The reverse rarely happens, the exception being the odd time a man serves a woman an alcoholic beverage. This is one of the dozens of things I keep track of in feature films and after analysing roughly 750 of them I can assure you: it is far, far more common in film to see women serving men than to see men serving women. If you’re wondering why this is, remember: the vast majority of movies are made by male filmmakers. They are very comfortable with the idea of women serving them and apparently allergic to the idea of men serving women. Thirdly, Wiest criticises her sons. You may not see this either—a woman criticising males—as significant but it is. Usually it is men who criticise women in film: art imitating life. And also because male filmmakers are fine with criticising women. Here Wiest does not let Haim get away with ruining her date with Herrmann without saying something about it. When she comes home in a rush at Haim’s insistence to find a mess in the kitchen, a mess her sons haven’t cleaned up, she says to him, “You know, I’ve just about had it with the both of you. What is this mess? You spill milk all over the kitchen floor and don’t even bother to clean it up? […] You know, it’s not fair. I would like to have a personal life, too.” This is not her only assertive moment. Those of you who are mothers of adult sons will appreciate this one: Wiest says to Patric, who was 21 at the time, “Well then, let’s act like friends. Let’s talk. […] Michael, look at me.” How often in film can you remember a woman asking a man to make eye contact with her? If you can name three occasions when this has happened leave me a comment. I would be really curious to hear about them. And yet, in ‘real life’ it is not uncommon for women to wish the males in their lives made better eye contact with them. But this is not something filmmakers often concern themselves with, so it’s nice to hear Wiest say the words here. The last inclusions I want to draw your attention to are the consideration a man shows for a woman and the male who stands up for a woman. Indeed, Patric says to Haim, “Come on, Sam, give mom a break” and Haim, defending Wiest, says to Herrmann, “Don’t you touch my mother!” The Lost Boys isn’t perfect and there are definitely things to criticise about it, beginning with the small number of female parts, but these days, when there is so little regard for women and girls in the ‘real world’ I’m happy to remember occasions in film when male characters showed consideration for women and stood up for them. We could use a lot more of that in the world today. My upcoming film guide for women contains 500 feature film reviews. I look forward to sharing my findings about mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries and what they have to offer female viewers. I will be making more videos about horror movies in the upcoming weeks because I am already getting excited about Halloween so if there is a film you would like to hear about please leave me a comment. Copyright © 2020 Alline Cormier Gremlins (1984) is a PG-rated comedy horror that runs one and three-quarter hours. The screenplay was written by Chris Columbus and directed by Joe Dante, who gave us The Goonies (1985) and Explorers (1985), respectively, the following year. It made over US$148 million at the American box office (keep in mind that this figure is in unadjusted dollars). It is set at Christmas in an enjoyable way, similarly to Home Alone (1990)—as opposed to Die Hard (1988) and The Lion in Winter (1968), which are also set at Christmas but lack a Christmassy feel. It tells the story of a teenager named Billy, played by Zach Galligan, who receives a unique, furry little creature for Christmas that multiplies and terrorizes his American town. If, like me, you’re a Gen-Xer, you’ll have fond memories of Gremlins. Depending on your age it may even be the first time Corey Feldman showed up on your radar. Back then he was as cute as Gizmo, the creature Billy’s father brings back from a business trip. Again, depending on your age you may have owned a Gizmo figurine or stuffed toy, as they were very popular. I had a figurine. There was quite a bit of merchandising. Perhaps not as much as for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial—I haven’t looked into it—but it certainly wasn’t negligible. It likely made Steven Spielberg, Gremlins’ executive producer, quite a bit richer than he already was. One wonders what he does with all that money. My film commentaries aren’t full movie reviews. Typically I shine a spotlight on just one aspect of the movie, for example, language, the sexualization of the female characters or violence against women and girls. However, for Gremlins I’d like to discuss a few different aspects, all of them relating to the female characters, of course. One of the things that interests me most about movies is the way the female characters are treated. Since Gremlins is such an old movie I’m not worried about spoilers. If you are you should probably stop listening now. Let’s start with women’s presence and voice. There’s only one exchange between women, and it is hostile (Belinda Balaski, who plays a very small role, asks Polly Holliday a question and Holliday responds meanly). If it doesn’t bother you that a feature length film only includes one exchange between women you should ask yourself this: how many movies can you name in which there is only one exchange between men? There are three significant named female characters and they are played by Phoebe Cates, Frances Lee McCain and Polly Holliday. Cates plays Kate, the protagonist’s love interest. McCain plays his mother, and Holliday plays the staple unlikeable old lady, named Ruby Deagle. She’s mean, lives alone with a bunch of cats and says things like, “I hate Christmas carollers.” She’s a rude and manipulative client at the bank where Billy works as a teller. Twice she threatens to kill his dog, saying she would like to give him a “slow, painful death.” Holliday has no likeable traits, and we are meant to dislike her, as is often the case with old women in mainstream movies. She’s sort of a cross between the crazy old cat lady and the wicked witch. This isn’t the only mean old lady Chris Columbus has given us. The next year, in The Goonies, it was ‘Mama Fratelli’, played by Anne Ramsey. In Gremlins, as per the established cinematic formula, the mean old lady is punished in the end, killed off in this case. Moreover, the scene in which the old cat lady is killed is meant to be funny. That’s right: the filmmakers use violence against women as a comedic device—not for the first time in film and far from the last. Here’s what happens: the gremlins, which are the mischievous and repulsive creatures that the cute, furry creatures eventually turn into, tamper with the stairlift in Holliday’s house and she zips up her stairs, screaming, before being ejected out a window into the street below. Her chair then appears on the sidewalk, with her legs and feet in the air. And we’re meant to enjoy the way she’s been treated because she’s such a horrible person. Here’s something else worth noting: as she zips up the stairs she passes a framed picture of a smiling man looking in the direction she is heading. He seems happy to see her going that way. This reminds me of the sticky end the Wicked Witch of the West comes to in The Wizard of Oz (1939). In that case the horrible, unlikeable old woman, played by Margaret Hamilton, was totally obliterated and viewers were meant to rejoice, as the film’s other characters did. These are just two examples of old woman murders among the numerous ones cinematic history has provided. Filmmakers often portray old women as terrible, unlikeable people and then treat them very badly to punish them. Now that our societies have made it illegal to kill women for being ‘witches’ it seems male filmmakers are finding consolation in murdering them on the big screen. There isn’t much to say about Phoebe Cates, the love interest. Sexualization isn’t really an issue here. Cates and the other female characters are modestly dressed throughout. She even wears a dress that is buttoned up to her chin. And McCain wears slacks and a cardigan over her dress shirt. Compare this with the way women are dressed in A Bad Moms Christmas (2017). We’ve come a long way in thirty-some years—a long way in the wrong direction as far as costumes are concerned. I miss the modest, comfortable outfits actresses got to wear in the ‘80s. Something worth mentioning about Phoebe Cates concerns the flasher scene: a gremlin in a trench coat exposes himself to her in a bar, and this is supposed to be humorous. Remember: the filmmakers are men. This sort of thing often appears to be funny to men—not so much to women. This kind of inclusion trivializes sexual predators. When I was in my early twenties I found myself in a bar, at a table with some male friends and a man I didn’t know joined our party and made a joke of putting his penis on the table for me to look at. He seemed to think his joke was hilarious but twenty-some years later I still haven’t forgotten how inappropriate and unwanted this attention was. It would be great if filmmakers would stop trivializing sexual harassment. If they took it seriously I suspect men eventually would, too. Another thing worth discussing is the gender roles. They are very traditional. Cates serves male gremlins beer and Frances Lee McCain makes supper and gingerbread cookies and hangs up her husband’s coat for him when he comes home. For some reason he’s incapable of doing this for himself. McCain regularly played moms in the ‘80s, for example in Stand by Me and Back to the Future. Here again she is a stay-at-home mom, and she appears in the kitchen a few times. It’s as if the filmmakers were pining for the 1950s that existed in TV and Movieland. McCain’s family has a Leave it to Beaver feel to it. In the ‘80s my own mother was working a full-time job and taking university classes. She didn’t spend much time in the kitchen, and she was hardly unique in this way. In Canada workplaces were full of women and there weren’t too many June Cleavers to be seen in real life. In Gremlins women with lines play a bank clerk/waitress, housewives and a professionless woman. Men occupy the dominant positions: a police sheriff and a bank manager. Other men with lines play: a bank teller, an inventor, a store owner, a teacher and a policeman. Both Frances Lee McCain and Phoebe Cates, like Polly Holliday, are victims of violence. Gremlins throw dishes at McCain and try to choke her and a gremlin shoots at Cates. McCain, a middle-aged woman, fares better than Holliday though. She gets to defend herself and kill the gremlins wrecking her kitchen. For once I didn’t mind filmmakers showing a woman using her blender and microwave. I also liked how she armed herself with a few knives, not just one. Unfortunately, she ends up having to be saved by her son. A female filmmaker, I believe, would have shown her ridding her house of gremlins on her own without the help of her teenage son. That would have been more progressive anyway. And it’s not as if women hadn’t successfully battled monsters in film at that point. Look at what Sigourney Weaver did in Alien (1979) five years earlier. Additionally, in an opening scene of Gremlins a random boy smashes a snowball over a girl’s head. This behaviour is meant to appear normal. What it actually does is normalize this type of behaviour. Gremlins gives us a grim Christmas but it’s amusing and well made and as far as horror movies go female viewers could do much worse. My upcoming film guide for women contains 500 feature film reviews. I look forward to sharing my findings about mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries and what they have to offer female viewers. It had been my intention to make this article funnier, as a way of honouring Magdalen Berns, who died of cancer one year ago today. Magdalen taught me a great deal about one issue in particular and introduced me to at least one amazing woman, for which I am very grateful. I highly recommend checking out her YouTube channel. She and her witty commentaries are greatly missed by many women I know. Copyright © 2020 Alline Cormier Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994) is an R-rated horror movie that runs two hours. It was directed by Kenneth Branagh and the screenplay, which is based on Mary Shelley’s novel, was written by Steph Lady and Frank Darabont. A few days ago it was Mary Shelley’s birthday. Shelley, née Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and daughter of the English author Mary Wollstonecraft, was born in London on August 30, 1797. Her novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, which she began in the summer of 1816, has inspired numerous film adaptations and related movies, including Frankenstein (1931), starring Boris Karloff as the Creature. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein Robert De Niro plays the Creature, Victor Frankenstein is played by Kenneth Branagh and Helena Bonham Carter plays Elizabeth, Victor’s adoptive sister and love interest. The story, set in Switzerland in the late 18th century, is about a scientist whose life is destroyed by his creation. This film made over US$112 million at worldwide box office. It has things to offer female viewers, but there are drawbacks. My film commentaries aren’t full movie reviews, and the aspect of this film that I want to shine a spotlight on today is violence against women. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein includes violence against women throughout, some of it quite graphic. The female characters do not fare well and this merits discussion. For starters it includes four deaths of women. Over and above these deaths, two of which are gynocides, women are victims of break and enter, assault and manhandling, all committed by males. The lead female (Helena Bonham Carter) suffers violence in several scenes. She dies a horrible death twice. Kenneth Branagh and Robert De Niro grab her in various scenes. De Niro breaks into her room, climbs on top of her in bed, clamps a hand over her mouth and rips out her heart. Branagh decapitates her with a meat cleaver. She also sets herself on fire with an oil lamp and runs down a hall, engulfed in flames, before falling from three stories to her death. She is not the only female character to fare badly. Trevyn McDowell, a secondary character, is dragged away by two men, then one puts a noose around her neck, men push her off a rooftop and she falls several stories to her death (in front of her mother). Also, Cherie Lunghi, another secondary character, dies in childbirth. In my upcoming film guide for women, which contains 500 feature film reviews, I discuss all kinds of things about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. I look forward to sharing my findings about mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries and what they have to offer female viewers. Copyright © 2020 Alline Cormier Stand by Me is an R-rated adventure drama that runs one and a half hours. The screenplay, written by Raynold Gideon and Bruce A. Evans, is based on a Stephen King novel. The film was directed by Rob Reiner and tells the story of four teenage boys who go looking for the body of a dead boy who went missing in Oregon earlier that summer. The boys are played by Wil Wheaton, River Phoenix, Corey Feldman and Jerry O’Connell. Stand by Me made over US$52 million at the worldwide box office (keep in mind that this figure is in unadjusted dollars. It is a very respectable sum). It was a very popular movie and is still well-known. Unfortunately, it has very little to offer female viewers. It scores poorly for women’s presence and voice. There are no significant female characters. Women get very few lines and no two women ever speak so it fails the Bechdel test—a test that serves as an indicator of the active presence of women in movies. The aspect of the film I’m going to shine a spotlight on today is the language used in reference to women and girls. This is one of the dozens of things I keep track of in feature films. Part of the reason for this is that language is very revealing about filmmakers. It tells us a lot about how well or poorly they think of women. The language in Stand by Me is coarse, sexist, sexualized and degrades women and girls. It demonstrates a lack of regard for women in girls that merits attention. Let’s examine the evidence. River Phoenix refers to his female teacher as a b*tch. To insult each other the boys call each other “girls” and “pussy.” A boy calls another boy a “son of a whore.” Wil Wheaton says, “Mayor Grundy barfed on his wife’s tits.” He says to his friends about vomit, “And then your mother goes around the corner and she licks it up.” He says to Kiefer Sutherland, “Why don’t you go home and f*ck your mother some more?” Teenage boys also say: “I think Annette’s tits are getting bigger”; and “[…] what a blimp. No shit. She looks like a Thanksgiving turkey […].” (The latter comment is made about the boy’s cousin.) Also, a boy says, “I’ve been seeing her for over a month now, and all she’ll let me do is feel her tits,” to which Sutherland replies, “You wanna get laid you gotta get yourself a protestant.” This type of language in reference to women and girls is common in mainstream movies and can be heard in many movies based on Stephen King novels. It does nothing to increase people’s regard for women and girls. Indeed, it normalizes disregard for women and girls. Moreover, it is worth noting that none of the female characters have a first name. Frances Lee McCain, who plays Wheaton’s mother, is credited as Mrs. Lachance. The other women are credited as: Waitress, Mayor’s Wife and Fat Lady. I look forward to sharing my findings about mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries and what they have to offer female viewers in my upcoming film guide for women, which contains 500 feature film reviews. Copyright © 2020 Alline Cormier As is the case for Stand by Me (1986) I really enjoyed The Goonies (1985) when it came out and have watched it more times than I care to admit. I was nearly a teenager at the time, just a few years younger than the lead characters (Mikey, Mouth, Chunk and Data). Like many people I feel like Goonies was part of my childhood. Like many girls I also developed a crush on some of the actors. But now, decades later, I’m able to take a more critical look at this beloved movie. Context: The Goonies is a PG-rated adventure comedy that runs nearly two hours. The screenplay, written by Chris Columbus, is based on a story by Steven Spielberg. It was directed by Richard Donner and tells the story of seven teenagers in Oregon who go looking for a pirate treasure after four teenage boys, all misfits, find a treasure map in an attic. The four misfits are played by Sean Astin, Corey Feldman, Jeff Cohen and Ke Huy Quan. The three that join them are Astin’s older brother (played by Josh Brolin), the girl he fancies (played by Kerri Green) and her best friend (played by Martha Plimpton). The Goonies made over US$62 million at the American box office (keep in mind that this figure is in unadjusted dollars). The Goonies scores well for females’ presence and voice and has a few things to offer female viewers: a few significant female characters; two tough, assertive females (namely Plimpton’s character, named Stef, and Anne Ramsey’s character, named Mama Fratelli); as well as exchanges between females. Stef in particular is a refreshing character and one that girls can easily identify with. Nowadays she would likely be considered gender non-conforming for her short hair, somewhat masculine clothes and tomboy-ish nature. She wears pants, a scarf and hoodie over her T-shirt, the kind of modest outfit filmmakers rarely give teenage girls. She is also clever and repeatedly puts an obnoxious boy in his place. Indeed, she silences Corey Feldman and calls him stupid. Both of these inclusions are rare in Hollywood movies. It is much, much more common for males to silence females and for females to be called stupid. And yet, there’s never any question about Stef’s sex. She’s a girl. She knows it, and so does everyone else. No one hints that she may be a boy trapped in a girl’s body. She just doesn’t conform to regressive stereotypes, as many girls didn’t in the '80s and many girls don’t now. There are drawbacks to this movie. It should be noted that these film commentaries aren’t full movie reviews. Typically I focus on just one aspect of films here, for example language, VAW or sexualization of women and girls. The aspect of The Goonies I want to shine a spotlight on today is the language used in reference to women and girls, which is one of the dozens of things I keep track of in feature films. Part of the reason for this is that language is very revealing about filmmakers. It tells us a lot about how well or poorly they think of women. Language in The Goonies is clean. It is also sexualized, demeaning and insulting of women and girls. This does not mean that it is sexualized, demeaning and insulting throughout, but rather that there is at least one example of sexualized, demeaning and insulting language at some point. Let’s examine the evidence. Corey Feldman tells his buddies they should be “[…] sniffin’ some ladies.” He says to Josh Brolin, who is kissing Keri Green, “Slip her the tongue!” He sticks his tongue through a hole in a painting of a woman and says to Sean Astin, “Come here and make me feel like a woman.” He also says to Brolin about his upcoming date with Green and his mom having to drive because he doesn’t have a driver’s licence, “[…] then you gotta make it with her and your mom.” He tells Jeff Cohen he has naked pictures of his mom taking a bath and will sell them to him, “real cheap.” He says to Plimpton as he holds a small mirror up to her face, “You wanna see somethin’ really scary, look at that.” He also says to her, “Your looks are kind of pretty—when your face doesn’t screw it up.” Moreover, Green calls Anne Ramsey, a much older woman, a “gross old witch.” Are these inclusions sufficient to ruin the movie? Not at all. Do they merit attention? Absolutely. There is a generalized lack of regard for women and girls in our societies and for the last five years I have been exploring the role movies play in this. I look forward to sharing my findings about mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries and what they have to offer female viewers in my upcoming film guide for women, which contains 500 feature film reviews. Copyright © 2020 Alline Cormier A Nightmare on Elm Street is an R-rated horror movie that runs one and a half hours. It was written and directed by Wes Craven. It is set in California and tells the story of two 15-year-old girls who are terrorized by a serial killer. The girls are played by Heather Langenkamp and Amanda Wyss. A Nightmare on Elm Street made over US$25 million at U.S. box office (keep in mind that this figure is in unadjusted dollars. It is a very respectable sum). It was a very popular movie and led to many sequels. In spite of all this it has very little to offer female viewers. The aspect of the film I want to shine a spotlight on today is clothing. Typically my film commentaries focus on either language, the sexualization of the female characters or VAWG but for once I’d like to talk about the actors’ costumes. In A Nightmare on Elm Street they weren’t brilliant and they couldn’t have won any awards but they do merit some discussion. Robert Englund, the actor who plays the infamous serial killer Freddy Krueger, is always fully dressed: he wears pants, a sweater, shoes and in most scenes a hat. The girls he hunts, on the other hand, are not so fortunate. The first time he chases Wyss she is barefoot and appears in nothing more than a nightgown. The next time he attempts to murder her she is barefoot and appears in just panties and a shirt. And when he hunts Langenkamp she is barefoot and wears nothing more than a pyjama. Although it is commonplace for men to be dressed more generously than females in film I found this case to be particularly remarkable. It is also worth noting that when Wyss is murdered (in just her panties and a shirt), she appears covered in blood and her ordeal is drawn out. Also, there is no funeral for her. The next murder victim is her boyfriend. This murder involves no blood and he wears jeans, a T-shirt, a leather jacket and running shoes. He also gets a funeral even though he is suspected of murdering Wyss. I imagine this is the type of thing males take no notice of but I would be very surprised if I were the only woman who found this strange. In my upcoming film guide for women, which contains 500 feature film reviews, I point out all kinds of things about A Nightmare on Elm Street. There was much to comment on. I’m still in the process of looking for a literary agent or a publisher but I hope to get my film guide out to you soon. There’s really nothing like it in bookstores and I’m looking forward to sharing my findings about mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries and what they have to offer female viewers. Copyright © 2020 Alline Cormier |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed