|

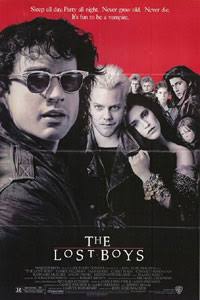

The Lost Boys is an R-rated horror movie that runs just over one and a half hours. It was directed by Joel Schumacher and the screenplay, which is based on a novel by Janice Fischer, was written by Fischer, James Jeremias and Jeffrey Boam. It made over US$32 million at the U.S. box office (unadjusted dollars). It is one of the rare horror movies I find enjoyable, and this is mainly due to its many humorous moments. Originality is another thing it has going for it. This isn’t the usual old-man-preying-on-much-younger-women vampire story. Consider the tagline: “Sleep all day. Party all night. Never grow old. Never die. It’s fun to be a vampire.” When The Lost Boys was released it felt like a fresh cinematic take on vampires. It came out five years before Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) and likely renewed audiences’ appetite for vampire movies. I suspect most North American Gen-Xers are familiar with it, but for everyone else I will provide some context before diving into what it has to offer female viewers. The Lost Boys tells the story of two teenage brothers, Michael and Sam, played by Jason Patric and Corey Haim respectively, who must deal with a group of vampires that Patric befriends when the brothers and their mother, played by Dianne Wiest, move to their grandfather’s house in Santa Carla, California, from Arizona after her divorce. The handful of vampires Patric starts hanging out with after dark are led by Kiefer Sutherland. The year before we had seen him in Stand by Me and the next year he was in Young Guns—both highly entertaining movies. This Sutherland is the grandson of Tommy Douglas, the Premier of Saskatchewan who was behind Canada’s first universal health insurance system—one of the things that makes Canada great. But I digress. Getting back to the boys, Corey Haim also befriends some teenagers: the Frog brothers, fighters for truth, justice and the American way while working in their parents’ comic book store. This second set of brothers is played by the camo-sporting Corey Feldman and Jamison Newlander. As another aside, Corey Haim was a Canadian actor from Toronto who had appeared in Lucas the year before. Corey Feldman has claimed publicly that Charlie Sheen raped Corey Haim on the set of Lucas when he was just 13 years old. Haim struggled with drug addiction in adulthood and died at the age of 38. I should mention that my film commentaries are not full movie reviews. Typically I shine a spotlight on just one aspect of the movie, for example, language, the sexualization of the female characters or violence against women and girls. For The Lost Boys I am going to focus on the progressive inclusions that relate to Dianne Wiest’s character, named Lucy. Also, I do not know if she is named Lucy as a nod to Bram Stoker’s novel (Dracula) but if you have read something about that please leave me a comment. I have not read any interviews with Janice Fischer. Since I am always very interested in how a movie scores for women’s presence and voice I will just point out quickly that it scores moderately well. There are only two named female characters (Wiest and Jami Gertz, Patric’s love interest), and they never speak. Also, there is no congeniality between women, women are harmed and Gertz is sexualized. In film women are often treated with little regard. The ‘80s and ‘90s, however, gave us a more progressive treatment of female characters and in some ways The Lost Boys is more progressive than many 21st century movies and has more to offer female viewers than many movies in the horror genre. I credit Janice Fischer with this. There is little focus on women’s looks here and relatively little sexualization of the female characters. The Lucy character and inclusions relating to her are of particular interest to me because they likely got little attention anywhere else. The first thing worth mentioning is the focus on the impoverished state she finds herself in after leaving her husband. There are undoubtedly scores of women who can relate to this situation. Her ex is alive but makes no appearance here. We only get Wiest’s side of the story. This is unusual. It is more common to be given the man’s version of events. Here we are shown a single mom struggling to raise her sons, so poor that she has to move back in with her father. We also see the 40-year-old getting a job as a cashier. The filmmakers lead us to sympathise with her and feel that she was unjustly treated. It may not seem like a big deal but more often than not filmmakers portray men’s blameworthy behaviour towards women approvingly, rather than disapprovingly. Secondly, and this, too, may not seem like a big thing but it is, Wiest sits down to a supper Edward Herrmann made her. Even though he made it off-screen this is still an improvement over what we usually get. Most often in film it is women who serve males food and drink. The reverse rarely happens, the exception being the odd time a man serves a woman an alcoholic beverage. This is one of the dozens of things I keep track of in feature films and after analysing roughly 750 of them I can assure you: it is far, far more common in film to see women serving men than to see men serving women. If you’re wondering why this is, remember: the vast majority of movies are made by male filmmakers. They are very comfortable with the idea of women serving them and apparently allergic to the idea of men serving women. Thirdly, Wiest criticises her sons. You may not see this either—a woman criticising males—as significant but it is. Usually it is men who criticise women in film: art imitating life. And also because male filmmakers are fine with criticising women. Here Wiest does not let Haim get away with ruining her date with Herrmann without saying something about it. When she comes home in a rush at Haim’s insistence to find a mess in the kitchen, a mess her sons haven’t cleaned up, she says to him, “You know, I’ve just about had it with the both of you. What is this mess? You spill milk all over the kitchen floor and don’t even bother to clean it up? […] You know, it’s not fair. I would like to have a personal life, too.” This is not her only assertive moment. Those of you who are mothers of adult sons will appreciate this one: Wiest says to Patric, who was 21 at the time, “Well then, let’s act like friends. Let’s talk. […] Michael, look at me.” How often in film can you remember a woman asking a man to make eye contact with her? If you can name three occasions when this has happened leave me a comment. I would be really curious to hear about them. And yet, in ‘real life’ it is not uncommon for women to wish the males in their lives made better eye contact with them. But this is not something filmmakers often concern themselves with, so it’s nice to hear Wiest say the words here. The last inclusions I want to draw your attention to are the consideration a man shows for a woman and the male who stands up for a woman. Indeed, Patric says to Haim, “Come on, Sam, give mom a break” and Haim, defending Wiest, says to Herrmann, “Don’t you touch my mother!” The Lost Boys isn’t perfect and there are definitely things to criticise about it, beginning with the small number of female parts, but these days, when there is so little regard for women and girls in the ‘real world’ I’m happy to remember occasions in film when male characters showed consideration for women and stood up for them. We could use a lot more of that in the world today. My upcoming film guide for women contains 500 feature film reviews. I look forward to sharing my findings about mainstream movies of the 20th and 21st centuries and what they have to offer female viewers. I will be making more videos about horror movies in the upcoming weeks because I am already getting excited about Halloween so if there is a film you would like to hear about please leave me a comment. Copyright © 2020 Alline Cormier

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed