|

One of the dozens of things I have been tracking about movies for my upcoming book on the sexualization of women/violence against women is actresses' ages. I have analysed 428 movies so far, which does not include all the movies I watched before I started writing my book over two years ago. One thing that always struck me about the cinematic landscape was the paucity of women over 40. For each movie I can name that stars a woman over 40 I can name at least 15 in which they are totally absent. Filmmakers have and still are overwhelmingly men. Female film stars have and still are, overwhelmingly, women under 40. The root of this is that women over 40 are past their sexual prime and therefore of little interest to male filmmakers. Because men prefer younger women, who fit the Barbie image better—and Barbie lookalikes being central to male fantasies—they are the ones filmmakers cast. This is patently obvious when one considers the age gap that separates Hollywood couples (and even male and female leads that are not paired romantically). Older men's love interests are now almost exclusively much younger women.

However, the sexist Hollywood age gap is not the only time older women are excluded from movies. Filmmakers also have a habit of avoiding casting older women when the story actually calls for one. For instance, in Forrest Gump (1994) Sally Field plays Tom Hanks' mother even though she is only ten years older than he is. In several other movies that cover decades of a person's life two or three actors play the character at various stages of their life, for example Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), in which River Phoenix plays Young Indy and Harrison Ford plays present day Indy. The same could have been done in Forrest Gump with Sally Field playing young and present day Mrs. Gump (in the credits she has no first name) and an elderly woman could have played elderly, dying Mrs. Gump. It is not as if there are no elderly women to be found in Hollywood. Most people can name many elderly male actors. Few people can name as many elderly actresses, with the notable exceptions of Meryl Streep, Sally Field, Jane Fonda, Shirley MacLaine, Helen Mirren, Judi Dench and Maggie Smith. As an experiment I challenge you to name, from memory, 20 actresses over 65 who have starred in a movie from the 21st century (no cheating with a search engine). Male filmmakers may be uninterested in seeing women over 40 on the big screen but I daresay they are of much greater interest to modern day female audiences. Baby boomers want to see women their age represented, and younger women are interested in seeing models of who they may become. Generally, we want to see the types of women who actually populate our lives. Why should women in their eighties and nineties be virtually nonexistent from movies when they make up a significant part of the human population? In Canada women’s life expectancy is around 82 years. Women over 65 made up 17.8 percent of the population in Canada in 2016, and yet movies are very far from reflecting this reality. Filmmakers have made Sean Connery, Harrison Ford, Tom Hanks, Jack Nicholson, Clint Eastwood, Morgan Freeman, Colin Firth, Anthony Hopkins, Robert De Niro, Liam Neeson, Bruce Willis, Dustin Hoffman, Ian McKellen, Gary Oldman, Ben Kingsley, Christopher Walken, Harvey Keitel, etc. welcome in their movies for decades—arguably when they were well past their sexual prime. In the 21st century we want to see women over 40 welcomed in the same way. It's time. © 2018 Alline Cormier

2 Comments

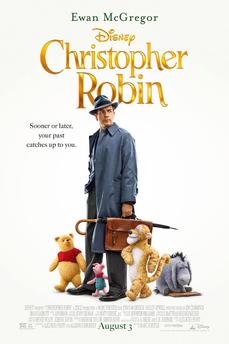

The trailer for the upcoming family movie Christopher Robin (2018) is the latest in a long string of new trailers in which women's presence is negligible. This is somewhat surprising considering how vocal women have been in the last year about being silenced. On the other hand it is a Disney movie, and Disney does not have a great track record for women's presence. In the trailer I watched yesterday no two women (or girls) are shown speaking. They talk to the male lead, Ewan McGregor, as well as several other male characters, but not to each other. One girl and one woman (the lead male's wife and daughter) will undoubtedly play a part in this movie but I wonder if their roles will be merely supportive, as they often are. I wonder if Christopher Robin will pass the Bechdel Test (a test that serves as an indicator of the active presence of women in movies). To pass it will need to show two female characters, preferably named, speaking to each other about something other than a male. This may seem like a very easy test to pass, the bar being so low, but it is astounding how many mainstream movies still fail. As I have written in a previous post (Oct. 4, 2017) this is the case for The Secret Life of Pets (2016), Kong: Skull Island (2017), Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014), Fast & Furious (2009), Indiana Jones and the Crystal Skull (2008) and The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), to name just a handful of movies that have failed this test.

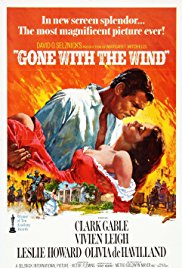

Christopher Robin (2018) looks like it will prove entertaining and magical. However, based on the trailer I am not convinced women and girls will occupy the place they deserve—in any story. We make up half the human race. Why shouldn't we take up half the space? Every movie should pass the Bechdel Test with flying colours. And if it does not strike you as odd that no two women ever speak in a two-hour movie ask yourself this: how many movies can you name in which no two men ever speak? © 2018 Alline Cormier Last night I started analysing Gone With the Wind (1939) and made it halfway through—to Rhett and Scarlett’s honeymoon. I had not watched it in years and had forgotten how much antagonism there is between women: in the opening scene Vivien Leigh (Scarlett) says she hates Olivia de Havilland (Melanie), which she repeats to herself later; Leigh and Evelyn Keyes (her sister Suellen) stick their tongues out at each other and Keyes eventually says she hates Leigh; and Alicia Rhett (India) tells Leigh she hates her. Moreover, this antagonism does not limit itself to verbal manifestations: Leigh pulls Keyes’ hair, she strikes Butterfly McQueen (Prissy) across the face and slaps Keyes.

Gone With the Wind won the Oscar for best picture that year along with seven other Oscars, including best writing (screenplay), best film editing and best director (along with best actress in a leading role and best actress in a supporting role). It made US$390.5 million at the worldwide box office (US$198.6 million in the U.S.), making it the highest-earning movie ever made—a distinction it held for over 25 years. According to Wikipedia it is the most successful movie in box-office history (when figures are adjusted for inflation). Furthermore, Hattie McDaniel, who won the award for best actress in a supporting role, became the first African American to win an Academy award. Its place in cinematic history can hardly be overstated. It is considered one of the greatest films of all time. For that reason I am giving it my full attention and have already taken five pages of notes. I think it set the tone for much of what would be made in subsequent years. Given the film’s importance the antagonism between women, violence against women and disparaging and insulting remarks directed at women become all the more unfortunate. (So far women have been called trash, a wench and a stupid fool.) The portrayals of women, too, are significant and merit attention. So far women have been shown crying sixteen times, nursing men and sewing and lying down (napping, sleeping) several times. They have appeared in their nightclothes. Men, on the other hand, have only been shown lying down when they are wounded or dead, and they are not shown in their nightclothes—at least, not yet. I can’t remember whether Clark Gable ever appears in a state of undress. Maybe the second half of the movie contains a scene in which Gable (Rhett) appears crying in bed in his pyjamas—but I rather doubt it. That type of portrayal is reserved for female characters. © 2018 Alline Cormier I recently analysed the latest screen adaptation of Stephen King's novel It. I had previously seen parts of the TV mini-series from 1990, so I had some idea of what to expect even though I have not read the novel. I knew it was a deranged story about an evil force that goes around killing a town’s children—an evil force that often appears as a clown. In this version women and girls play a very small part. There is only one significant female character: a 15-year-old who hangs out with a group of six boys. These seven kids are the lead characters. Women play secondary characters: stay-at-home moms and a librarian. Other notable characters are the aforementioned clown, played by a man, three male teenage thugs and a couple of fathers. The girl is typically surrounded by males. In the only scene she appears in with other girls her age they have hostile, antagonistic exchanges. A girl calls her trash and a slut. Another girl dumps the contents of a garbage bag over her head in a girls’ lavatory. This is not the only verbal abuse hurled her way. A woman calls her a "dirty girl" and a teenage boy says to her, "F*ck you, b*tch." She is also the victim of physical violence: a man grabs her by the neck (twice); her father sexually abuses her (alluded to, not shown); an evil force pulls her head into her bathroom sink before projecting a stream of blood in her face; and she is abducted, assaulted and an attempt is made on her life (in at least two scenes). So females are barely present, and the one who gets the most screen time is continually disparaged or harmed. Sexualization of women and girls is also an issue. The teenage girl, a victim of incest, is the only character to appear in a bath—a Hollywood staple usually reserved for women. She also strips down to her bra and panties in front of a group of boys and then sunbathes before them while they sit around watching her. Apparently in the book they all have sex with her in one scene. Thankfully this was left out of the film adaptation. Even a female character who is barely present, one of the moms, is sexualized: a boy says to another about an activity he wants to engage in over the summer, “Beats spending it inside your mother.” Also, a boy asks another, “Do you use the same bathroom as your mother? […] Then you probably have crabs.” Stephen King is hailed as the 'master of horror' and that may be fitting but what he also excels at is slighting women and girls and having men harm and terrorize them. A few years ago the United Nations declared a pandemic of violence against women (VAW). Instead of bringing King's deranged stories to the screen filmmakers would do well to make movies in which women and girls are respected and cherished. © 2018 Alline Cormier |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed